How to Use Cash in a Portfolio

A look at the pros and cons of the safest asset class, plus our favorite options.

Editor’s Note: A version of this article was published on Aug 28, 2023.

Should you have cash in your portfolio? It depends. Many investors don’t need to load up on cash if they’re saving for long-term goals, but cash plays a critical role for retirees and other investors with shorter-term spending needs.

In this series on portfolio basics, I’ll explain some of the fundamentals of putting together sound portfolios. I’ll start with some of the most widely used types of investments and walk through what you need to know to use them effectively in a portfolio.

What Is Cash?

Cash doesn’t only refer to the bills in your wallet. The term is broadly used to describe not just hard currency but other safe, liquid holdings such as Treasury bills, money market funds, and bank accounts.

There are a lot of these assets out there. Based on the most recent quarterly report from the Federal Reserve, US households own about $4.5 trillion in checking accounts and US currency, $9.7 trillion in savings accounts and short-term instruments, and $4.1 trillion in money market funds. If you added in assets held by corporations, nonprofits, and other organizations, those totals would be even higher.

What Are the Advantages and Risks of Holding Cash?

Cash has two main advantages: safety and liquidity. The US dollar is perceived as a safe asset because while it’s not backed by any physical assets, it’s supported by the full faith and credit of the US government. Outside of the United States, the US dollar is a major reserve currency, meaning large amounts of dollars are held by central banks and major financial institutions to use for international transactions. Because the US dollar plays such a key role in the global economy, it’s generally considered to be a reliable store of value globally.

Cash is also safe because it essentially never loses value, at least in nominal terms. Moreover, cash is the most liquid asset. You can easily spend US dollars. You can also easily access cashlike assets, such as checking accounts, savings accounts, and money market funds, to make purchases, asset transfers, and debt payments.

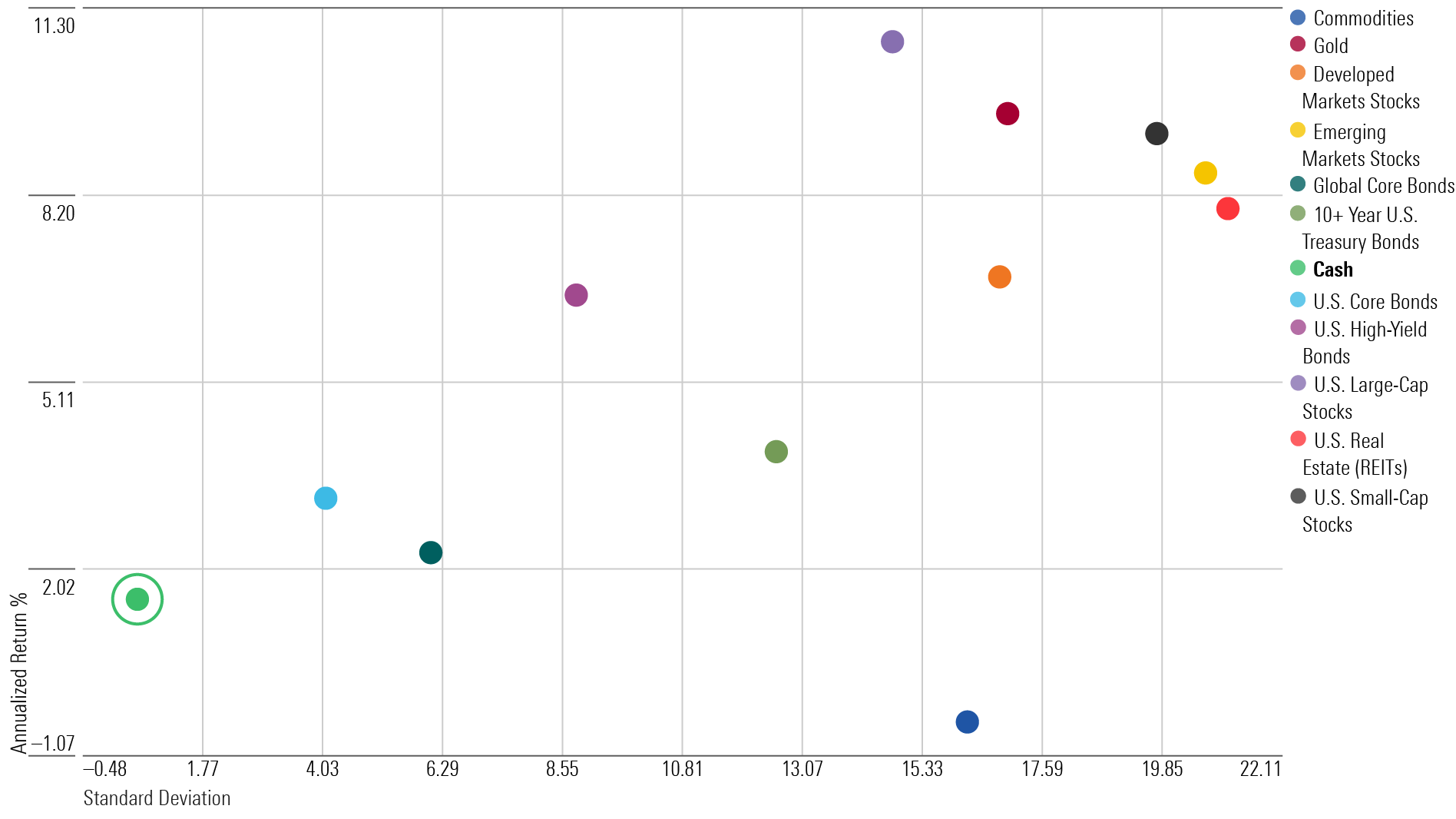

This safety comes at a price: lower returns. As shown in the chart below, cash has both the lowest risk and the lowest returns of any major asset class over time.

Trailing 20-Year Risk and Return: Cash and Other Assets

Because cash has no potential for capital appreciation, returns on cash are driven by yield. Over the past 40 years or so, yields on the three-month Treasury bill have ranged from a high of 16.3% in May 1981 to a low of 0.002% in May 2015.

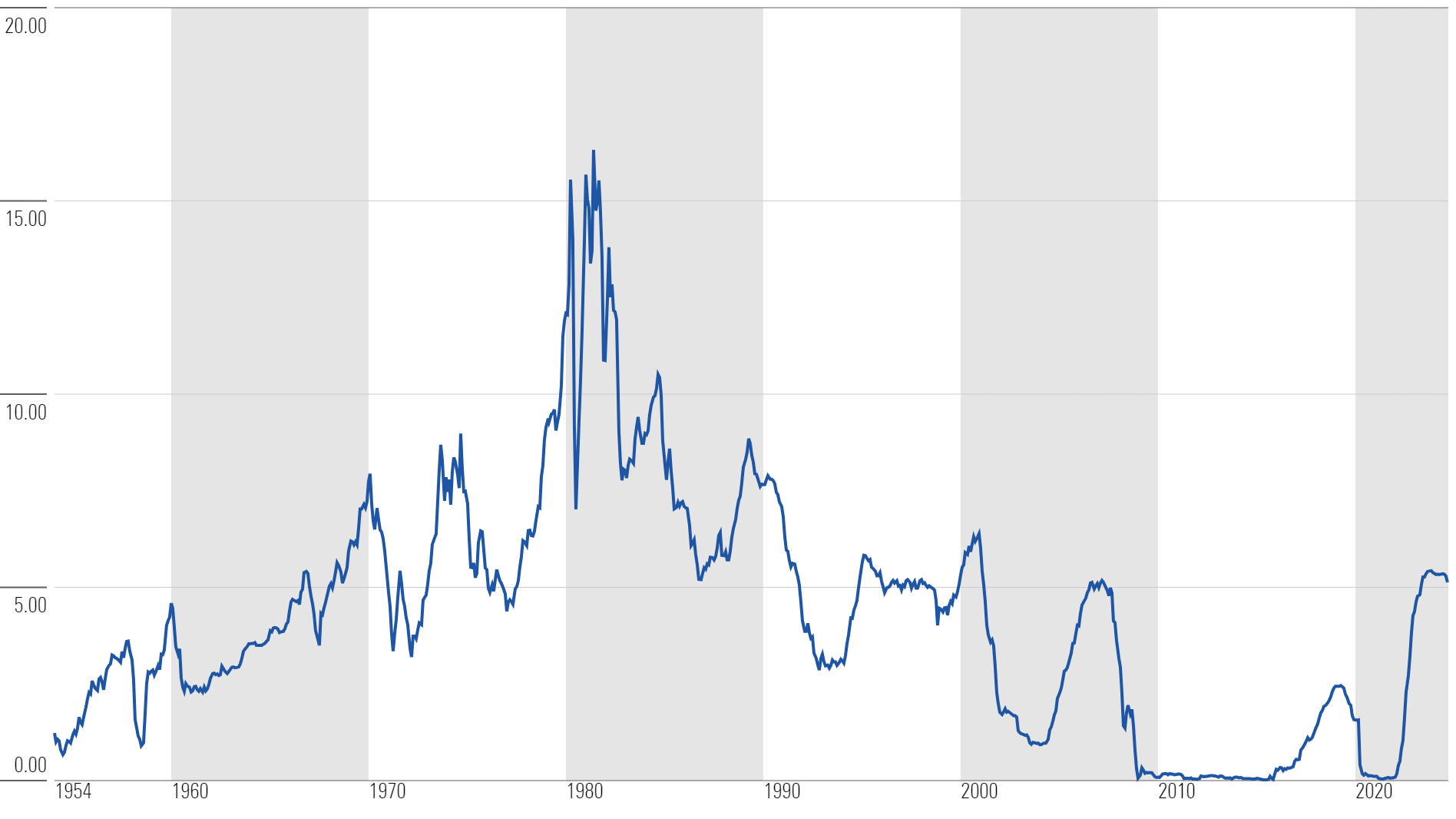

After the Federal Reserve made a series of aggressive interest-rate hikes starting in early 2022, the target federal-funds rate increased by more than 500 basis points. (More on how this works in the next section.) As a result, the three-month Treasury bill yield reached 5.36% on Oct. 6, 2023, which was actually higher than the year-over-year inflation number as of the same month. Yields have since edged down but were still elevated as of Sept. 18, 2024; rate cuts from the Fed point to further declines in Treasury yields.

3-Month Treasury Bill Yield Since 1954

But holding cash isn’t usually a good way to stay ahead of inflation, as shown in the table below. Because yields on short-term securities have been so low (until recently), annualized returns for cash have fallen behind inflation over most of these trailing periods. That said, returns on cash have edged slightly ahead of inflation if you look at the entire 97½-year period between January 1926 and now.

Annualized Returns for Cash vs. Inflation (%)

| Benchmark | Year to Date | 1 Year | 3 Years | 5 Years | 10 Years | 15 Years | 20 Years | January 1926 – July 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cash | 3.21 | 5.52 | 3.20 | 2.16 | 1.50 | 1.02 | 1.49 | 3.27 |

| Inflation | 2.40 | 2.76 | 4.79 | 4.13 | 2.80 | 2.55 | 2.56 | 2.95 |

Source: Morningstar Direct, Ibbotson Indexes. Data as of July 31, 2024.

When Does Cash Perform Best?

As mentioned above, yield is the main driver of cash returns.

The yield on cash is partly driven by Federal Reserve policy since the target federal-funds range sets the rate for overnight bank lending, which has a major impact on borrowing costs and overall financial conditions. As a result, the federal-funds rate indirectly affects short-term interest rates for cash and other securities. However, current yields on short-term Treasuries and other cashlike assets also reflect the market’s expectations for future inflation and interest rates. Some of the most generous periods for cash returns were in the 1970s and 1980s, but those periods were also marked by above-average inflation.

Annualized Returns for Cash and Inflation by Decade (%)

| Benchmark | 1930s | 1940s | 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | Jan. 2020 – July 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cash | 0.55 | 0.41 | 1.87 | 3.88 | 6.31 | 8.89 | 4.92 | 2.51 | 0.52 | 2.18 |

| Inflation | -2.04 | 5.36 | 2.22 | 2.52 | 7.36 | 5.10 | 2.93 | 2.43 | 1.75 | 4.48 |

Source: Morningstar Direct, Ibbotson Indexes. Data as of July 31, 2024.

How Long Should I Plan to Hold On to My Cash Assets?

Morningstar’s Role in Portfolio Framework considers cash to be the only suitable asset for holding periods of 12 months or less. If you have a spending need coming up a bit further out, such as within one to two years, cash might also be the best parking spot.

And it’s always important to keep some cash on hand to cover unexpected emergencies, such as job loss, car repair, appliance replacement, and so on. Most financial advisors recommend keeping at least six to 12 months’ worth of living expenses in cash as an emergency fund—even if you don’t end up spending it right away.

How Much of My Portfolio Should Be in Cash?

The answer to this question largely depends on your life stage. If you’re many years away from retirement, you don’t need to allocate much to cash, assuming you already have an emergency fund set aside, as well as enough liquid assets to cover any short-term spending needs.

Setting aside cash gets more important as you get closer to retirement age. Financial advisors typically recommend that retirees keep at least one to two years’ worth of expenses in cash or other low-risk assets. The reason? Holding cash gives you a ready source of liquidity for short-term spending and means you don’t have to sell stocks or bonds when the market is down.

Where’s the Best Place to Stash My Cash?

The table below shows some of the pros and cons of various ways to hold cash.

Where to Keep Your Cash

| Location | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Under the mattress or hidden in the attic | Easily accessible if you need to flee during a natural disaster. | Poor returns and risk of theft. |

| Bank savings account | FDIC insured up to $250,000 (per depositor, per bank). | Poor returns. |

| Money market account | FDIC insured up to $250,000 (per depositor, per bank); may offer check writing. | Most returns are still relatively low. |

| Certificate of deposit | FDIC insured up to $250,000 (per depositor, per bank); can lock in the current rate for a set period. | May require a minimum investment amount; penalty for early withdrawal. |

| Money market fund | Better returns than other cash options; easy to transfer assets to other accounts. | Not FDIC insured; small risk of capital loss (“breaking the buck”). |

| Treasury bills | Better returns than other cash options; can be purchased directly from US Treasury or most major brokerage firms. | Can’t be easily transferred; need to sell bills first before transferring or spending. |

What Funds Pair Well With Cash?

If you’ve already set up sufficient cash reserves, a US large-cap stock fund, international-stock fund, or bond fund could be a logical addition.

- US large-cap stock funds: These funds are a key foundation for nearly every investor’s portfolio. They’ve produced outstanding total returns over time and are one of the best ways to generate wealth for long-term financial goals. As mentioned above, US stocks currently make up about 60% of global market capitalization, so we consider them core holdings that could make up the majority of a portfolio’s equity exposure.

- International-stock funds: Stocks located in markets outside the US currently make up about 40% of the global market based on the value of shares outstanding. That makes them worth owning for the sake of getting more complete exposure to equity markets around the world. International stocks can also provide diversification benefits (especially as a hedge against weakness in the US dollar) and exposure to leading companies outside the US.

- Bond funds: These funds typically help buffer against losses in years when the stock market is down (although rising interest rates and unexpectedly high inflation led to sharp losses for both stocks and bonds in 2022). Bond funds have also often had negative correlations with the equity market, which can help improve risk-adjusted returns for a portfolio that includes both stocks and bonds.

Should I Hold Cash in My Portfolio?

You should hold some cash, but it’s not really an investment asset because of its lack of growth potential. That means that you can think of your cash holdings separately—not as a core component of your investment portfolio. While the generous yields currently available on cash may be tempting, keep in mind that it doesn’t generate enough growth to help fuel long-term capital appreciation.

5 Surprising Investments That Shouldn’t Be Long-Term Core Holdings

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/SIEYCNPDTNDRTJFNF6DJZ32HOI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/5WFC7QPLI3Z7OFQIJYFW66JXOY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6NA5G6FG6VH3ZJZJCDGJY4GMYA.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)