Is a Contrarian Approach to ETF Investing Right for You?

Standing alone invites challenges and market-beating potential.

“I will tell you how to become rich. Close the doors. Be fearful when others are greedy. Be greedy when others are fearful.”

Warren Buffett

Contrarianism means walking tall into prevailing winds. It requires an independent streak and comfort in parting from the herd.

These days, fearful markets aren’t common. Marketwide opportunities came up twice over the past 20 years—the global financial crisis and the coronavirus drawdown in March 2020. That said, Buffett’s advice is fantastic—if not immediately actionable. Wait for a fat pitch and swing for the fences.

Contrarian investing often comes down to mean reversion: Buy things priced lower than normal and sell when they’re abnormally high. For that reason, value investing is often conflated with contrarian investing. Value investors buy cheap stocks, often going against the market’s humble outlooks that are reflected in their prices.

But buying a cheap stock or exchange-traded fund isn’t necessarily contrarian. An investor who bought GameStop GME on the last day of 2020 would have received a 6% discount on GameStop’s price/book ratio relative to the Morningstar US Market Index, but it would have come on the heels of a 360% gain over the previous five months. (GameStop’s price/book ratio increased to 3.69 from 0.60 during that time.)

Likewise, it is not necessarily contrarian to buy a cheap stock without expecting its valuation to increase. Imagine I told you that you could buy the Morningstar US Utilities Index today at a 50% discount to the Morningstar US Market Index: Would buying it be a contrarian play? Not really. Its current price/book ratio is higher than its monthly average since 2000, meaning its portfolio of utilities stocks is expensive relative to its history. Utilities are also highly regulated, and their valuations are range-bound, making a significant payoff unlikely. With the Morningstar US Market Index’s valuation near historic highs, the contrarian play here could be moving out of US stocks and into foreign markets.

A high valuation doesn’t kill an investment—a high price relative to realistic expectations does. The same goes for a cheap stock whose low expectations still appear too high. Benjamin Graham and a young Warren Buffett found their niche in “cigar butt” investing, turning junk into gold with their Midas touch. But short-sellers can also be contrarians. They have a long history of finding trouble beneath the surface of a company’s financial statements and getting rich by shorting its stock, even when the price multiple looks cheap. A cheap stock is still overvalued when the company is worthless.

Therefore, contrarian investing is not value investing. Contrarian strategies thrive on a behavioral edge over the market by accepting, not relishing, the discomfort that comes from standing alone on an investment thesis. It’s not for everyone. But disciplined investors can use it to their advantage in the stock market, where they are almost always at a disadvantage to professionals in terms of information and resources.

John Templeton: A Pioneer of Contrarian Investing

“When people are desperately trying to sell, I buy. When people are desperately trying to buy, I sell.”

John Templeton

The above quote is eerily similar to Buffett’s quip about being fearful when others are greedy. Templeton built his empire on the back of a few courageous contrarian decisions. In 1939, Templeton put his contrarian ideals to work. The US was at the tail end of the Great Depression, and World War II had just broken out in Europe. While others panicked, Templeton saw an opportunity. He borrowed money and told his broker to buy 100 shares of each company trading for $1 per share or less on the New York Stock Exchange, which included 104 companies—34 of which were in bankruptcy.

Templeton knew the market was oversold due to fear, but he wasn’t particularly certain about any one company. So, he diversified his contrarian play by buying 104 companies, and only four ended up worthless. The rest were hugely profitable.

In the 1950s, Templeton again zigged while the rest of the world zagged. Japan had suffered a devastating loss in World War II, and investors looked down on its economy and prospects as a result. Templeton saw a promising workforce and a market whose stocks traded at a fraction of the price of US stocks. Even better, he discovered that Japanese companies didn’t include subsidiaries in their financial reporting, perhaps understating their assets and profits.

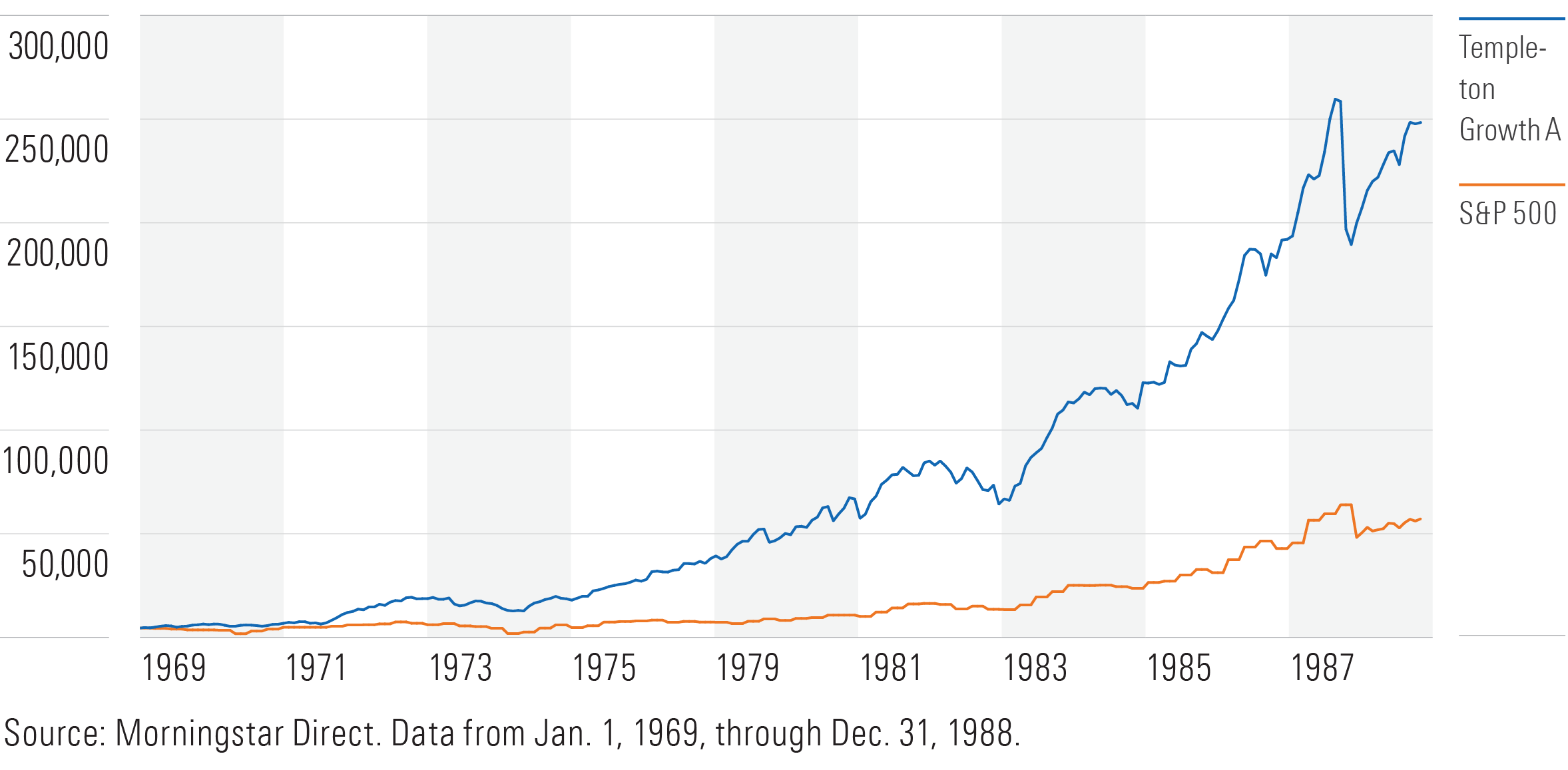

Templeton went nearly all-in on Japan with his personal money, and it paid off handsomely. Solid returns in the 1950s led to stagnant performance in the 1960s for Japanese stocks, a time when public opinion of Japan was in the dumps. Instead of cashing out, Templeton bought up Japanese stock for client funds as well in 1968, once the Japanese government allowed foreign investment. The Templeton Growth fund never paid more than 3 times earnings for Japanese shares and soon half of its portfolio consisted of Japanese stocks. The rest was history. Templeton Growth earned 17.5% annualized over the next 20 years, nearly doubling the S&P 500′s performance as the Japanese market exploded.

Growth of $10K for Templeton Growth and S&P 500

Most investors would not have the patience to let their thesis play out over the course of decades, especially when performance slowed in the 1960s. They can learn a lot from the success of Templeton’s independent thinking: Find an edge and don’t let go, even when everyone thinks you’re wrong.

Contrarian Investing Isn’t for Everyone

Most investors shouldn’t expect to uncover accounting peculiarities or dive deep into foreign markets. And investors with short time horizons certainly can’t sit out a decade or more of poor returns. However, investors can still benefit from smaller opportunities than those Templeton faced by adopting a contrarian perspective and sticking with it.

To start, investors should have an idea of what is out of favor. That often means buying into what hasn’t worked recently. US stocks have been hugely successful over the past 15 years. Overweighting foreign stocks would be contrarian. Public opinion is stacked against China, making it an interesting time to buy in. Significant risks in China exist, so care should be taken before investing there. Small-value stocks are currently the cheapest spot on the Morningstar Style Box; investors could find opportunity there.

A Contrarian Approach to ETF Investing

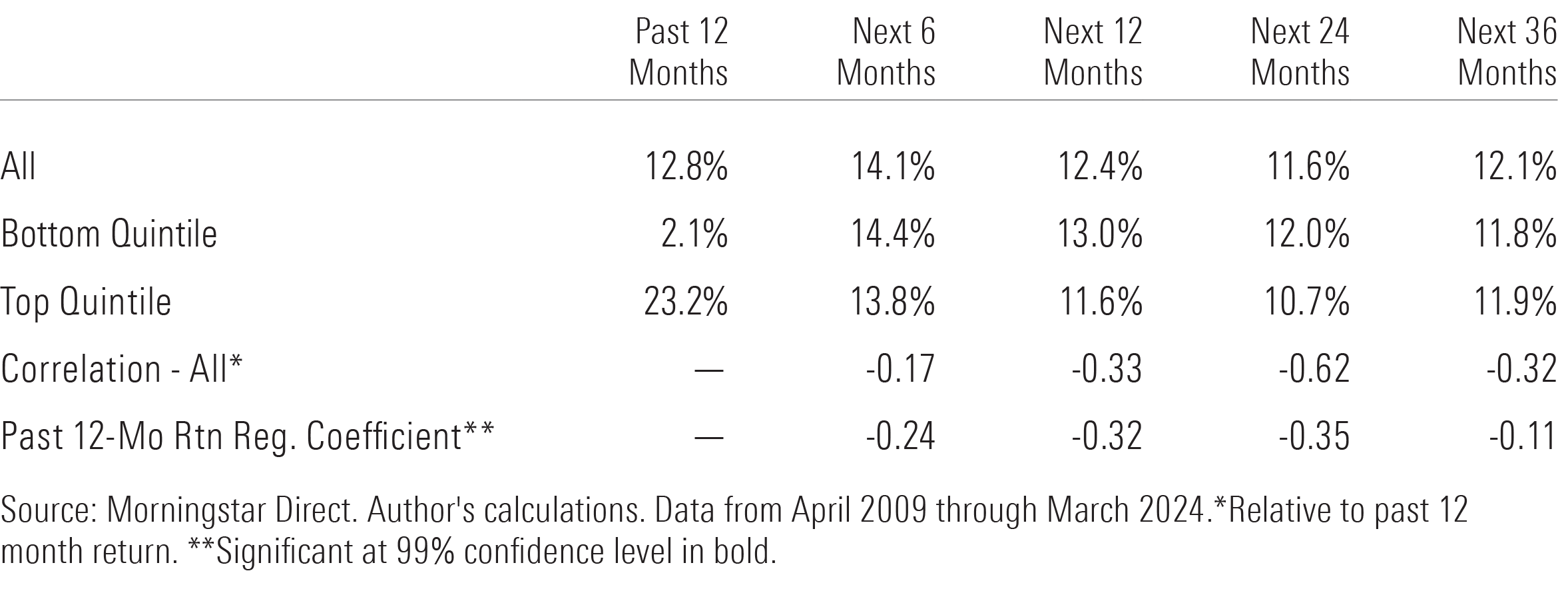

Another route is to simply buy exchange-traded funds with the worst recent performance. To see whether ETF investors could deploy a simple mean-reversion strategy, I compared the forward performance of US equity ETFs with their recent past returns. I broke the universe into top- and bottom-quintile performers over the trailing year, then compared their performance over the following six, 12, 24, and 36 months. I then ran regressions to see how future performance was affected by past performance, collecting the correlation of past and future performance and the strength of the coefficient. Given the ETF market has a relatively short track record, I ran this analysis over the past 15 years, which is summarized, below.

Annualized Forward Returns of ETFs Based on Recent Performance

ETFs in the bottom quintile by past performance ended up outperforming the rest over the following six, 12, and 24 months. This demonstrates the efficacy of being a contrarian when picking ETFs. And the top-performing quintile of ETFs underperformed the broader group, demonstrating the risk associated with performance-chasing.

The results showed a negative relationship between trailing 12-month performance and each iteration of future performance. The strongest relationship of mean-reverting performance existed with returns over the following 24 months, where the correlation was negative 0.62 on a scale from negative 1 to 1.

Based on the strength of the regression coefficient, the contrarian signal decays significantly by 36 months. Exiting a contrarian trade after one to two years appeared to be the ideal range to capture the benefits of mean reversion.

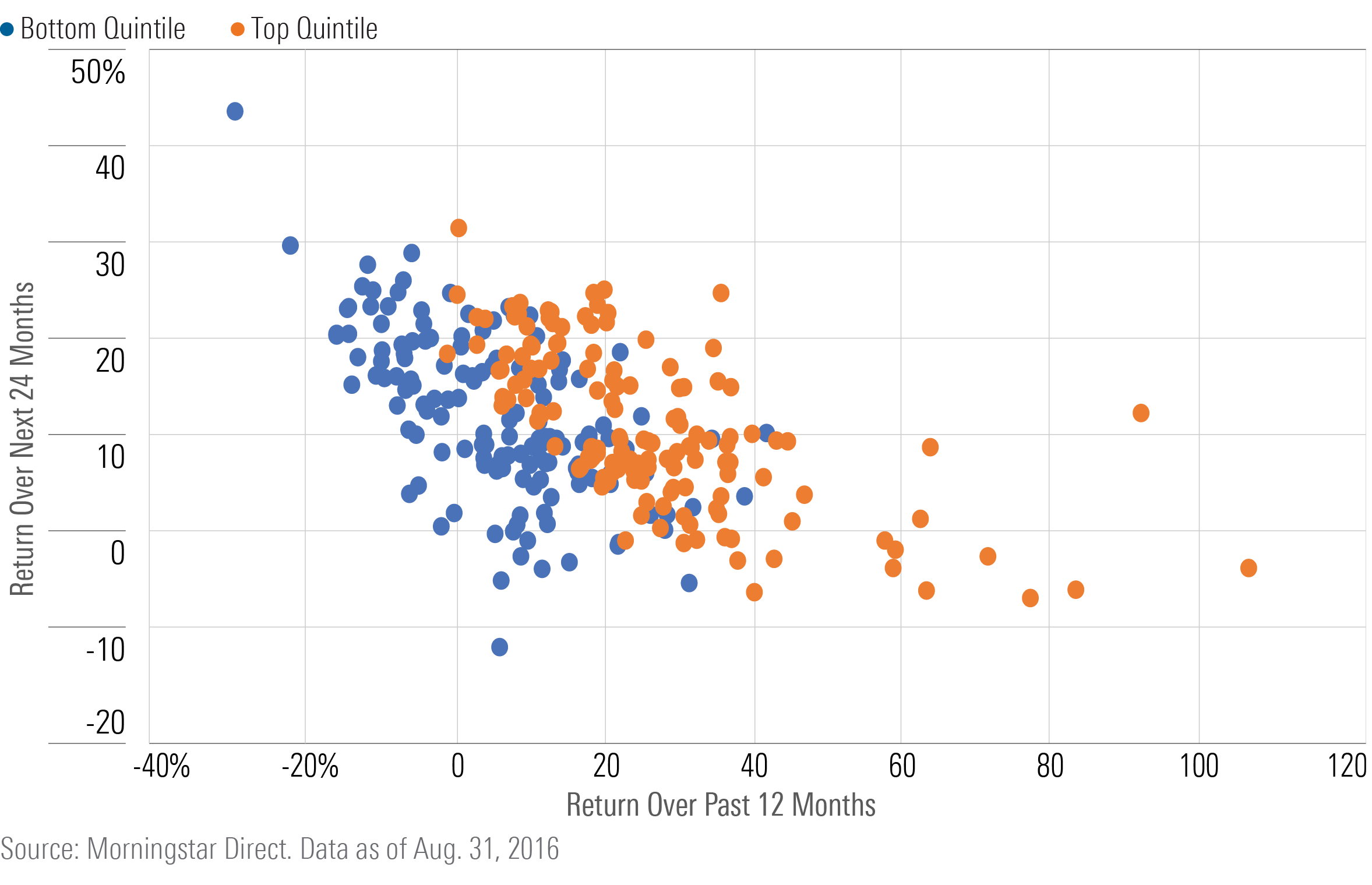

I also plotted the 24-month return against the prior 12-month return for the bottom-quintile (blue) and top-quintile (orange) past performers at the end of each month. The relationship between past and future performance is clearest at the extremes: Top-quintile performers were most likely to decline the following 24 months after strong performance (that is, greater than 40% return over the past year), and bottom-quintile performers did best after a 12-month losing streak.

Link Between Past and Future Returns

Contrarianism works best at the extremes. Investors should patiently wait for the odds to shift significantly in their favor. There will be many chances to go against the grain, but the most important times to swing are when fat pitches come right down the middle of the strike zone. Don’t fear standing alone when those opportunities show up.

This article first appeared in the May 2024 issue of Morningstar ETFInvestor. Download a complimentary copy of ETFInvestor by visiting this website.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/0fa19b38-60f6-4a0f-9e06-9869d9c57d52.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/NPR5K52H6ZFOBAXCTPCEOIQTM4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/09-24-2024/t_c34615412a994d3494385dd68d74e4aa_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/0fa19b38-60f6-4a0f-9e06-9869d9c57d52.jpg)