It's Not the 2008 Global Recession All Over Again

Risks are far lower than during the last U.S. financial crisis, despite COVID-19's impact.

The 2008 global recession left deep psychological scars on investors, many of whom have spent the last decade searching for signs that the next crisis is coming.

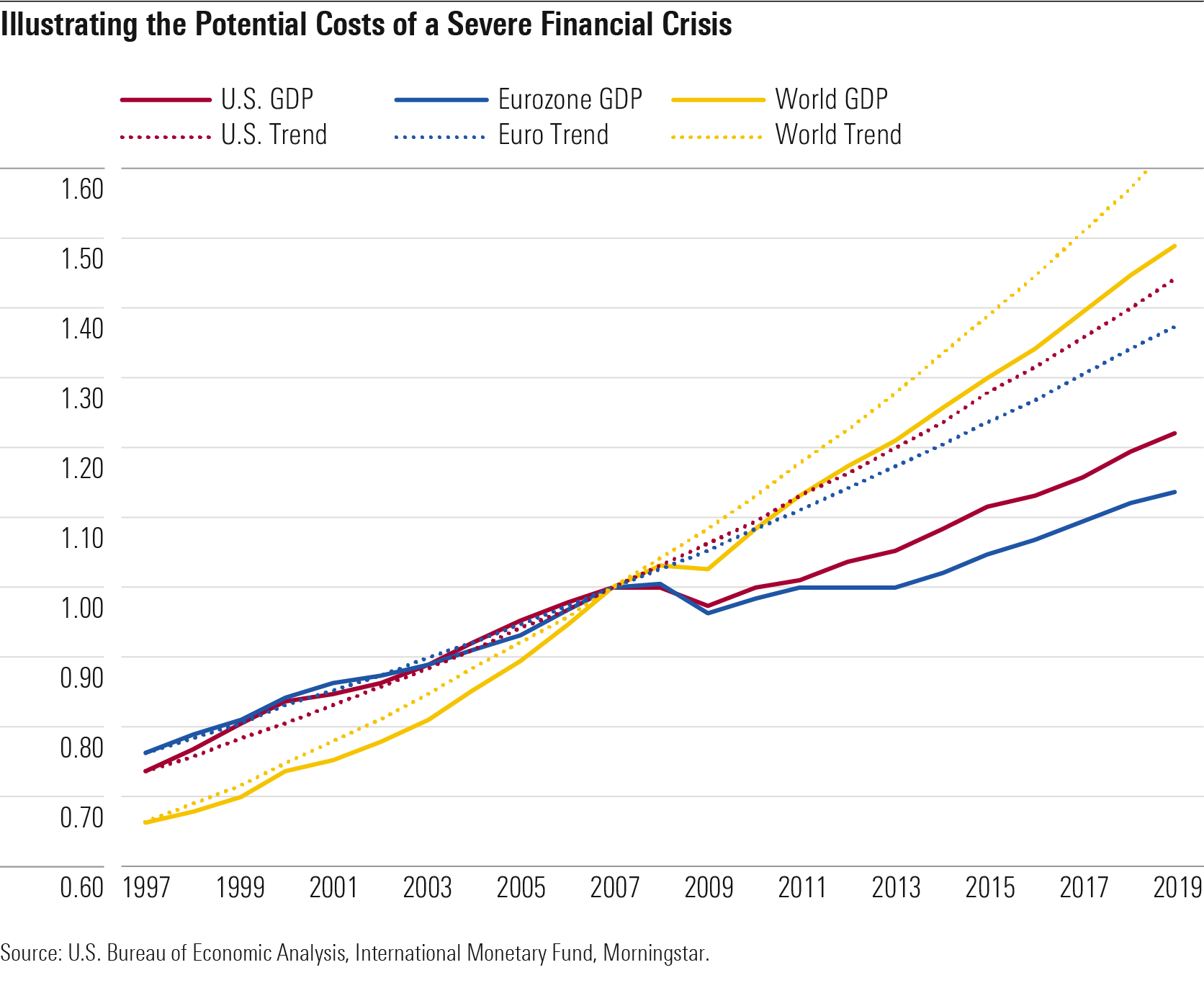

It’s been well documented that a severe financial crisis tends to cause the worst economic outcomes over the short to medium term and encourage worse results over the longer term. This is why it’s so important to gauge the probability of another financial crisis, because if it occurred, it would very likely influence the future economy for the worse.

While the chances of another long-term economic downturn are never zero, investors are fighting a repeat of the last war by focusing on financial crisis risks. Our analysts' current thinking is that the United States will avoid a financial crisis this time around, and the following evidence supports this thesis.

Illustrating the Potential Costs of a Server Financial Crisis

No Concerns About Rewarding Bad Behavior Ultimately, the Federal Reserve has the ability to largely prevent any financial crisis by virtue of its ability to supply unlimited liquidity to the financial system. This raises the question as to why the Fed ever allows financial crises to happen, given the severe economic costs.

Well, the primary answer is the moral hazard problem, where bailouts and other interventions reward bad behavior by protecting financial system participants from the consequences of their own actions. The provision of unlimited bailouts would corrode the long-term efficacy of the financial system in allocating capital and managing risk, essentially undermining the financial system’s fundamental role in the economy. In nearly every crisis, the Fed faces a trade-off between short-term financial crisis costs (reduced by intervention) and long-term moral hazard costs (increased by intervention).

However, the moral hazard problem is virtually nonexistent in the case of the COVID-19 recession, and this explains the Fed's massive and unconstrained response to the crisis so far. Very few financial system participants can be held responsible for the distress they are encountering during this recession, given that the pandemic is a shock coming from outside of the financial system and economy altogether. This is in sharp contrast to the 2008 global recession, when the recession and financial crisis were due primarily to irresponsible behavior in the financial sector. By and large, we expect the Fed to continue to do whatever it takes to shore up the stability of the financial system.

Fed Has Stepped Up Support for International Financial System One key caveat to the view that the Fed will do essentially whatever it takes to keep the financial system stable is that its ability to prevent a crisis from starting in the international financial system--which could possibly spread to the U.S.--is relatively limited. For various reasons, mostly political and legal, the Fed can't provide direct support to private foreign financial institutions or to foreign asset markets. Still, the Fed has expanded its support for the international financial system in recent years in crucial ways.

In recent years, the Fed has progressively expanded its dollar swap lines, which select foreign central banks can use to borrow U.S. dollars. Swap line borrowing rose substantially through April 2020, reaching levels only modestly below the prior December 2008 peak. While the surge in the U.S. dollar in March indicated a squeeze on dollar liquidity in global markets, most of that pressure has abated since then, thanks partly to the Fed’s help.

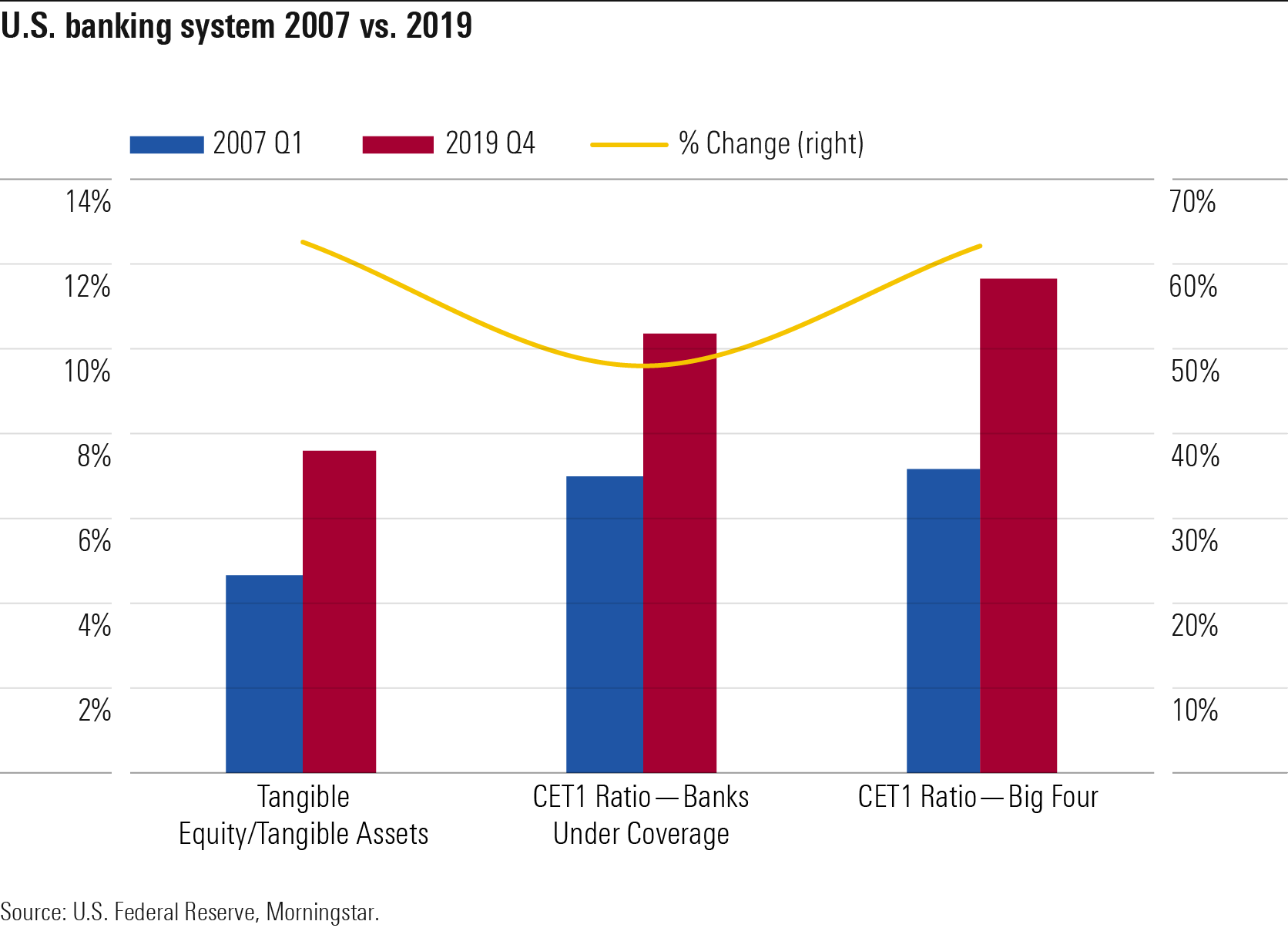

U.S banking system 2007 vs. 2019

Banks Are Better Capitalized and Less Leveraged Than Before While capital levels are much higher than they were in 2008, are they enough to cover the potential risks being taken? We think the balance of risk lies in the commercial sector. One of the main areas of concern in commercial lending is leveraged lending, where risks are elevated. In contrast to the 2008 global recession, where the highest risks were primarily concentrated within the banking system (and within a few large banks at that), the risks today are generally being taken by nonbanks. Banks are small holders of leveraged loan balances compared with other players.

The banks do hold some additional indirect exposure to leveraged loans by virtue of their ownership of collateralized loan obligations. Banks held 15% of U.S. CLOs as of 2018 per the Fed's analysis. However, 62% of CLOs were held by investors like insurance companies, mutual funds, or households. Thanks to their long-term liabilities (insurance companies) or lack of leverage (mutual funds and households), these investors have a relatively higher tolerance for losses. Lower risky balances and higher capital levels should make the system much harder to break this time around.

Shadow Banking Practices Have Been Regulated A major issue in the 2008 financial crisis was shadow banking, in which many nonbanking financial institutions were engaged in bankinglike activities. Shadow banks were highly leveraged and relied upon short-term (or redeemable on demand) liabilities, similar to a traditional deposit-taking commercial bank. Unlike officially chartered banks, shadow banks were not protected by deposit insurance. This made them vulnerable to classic bank runs, and indeed several shadow banking institutions (notably prime money market funds) faced runs during the 2008 financial crisis.

Thanks to increased regulation, among other factors, we think the shadow banking threat from the nonbanking financial sector is much diminished compared with 2008.

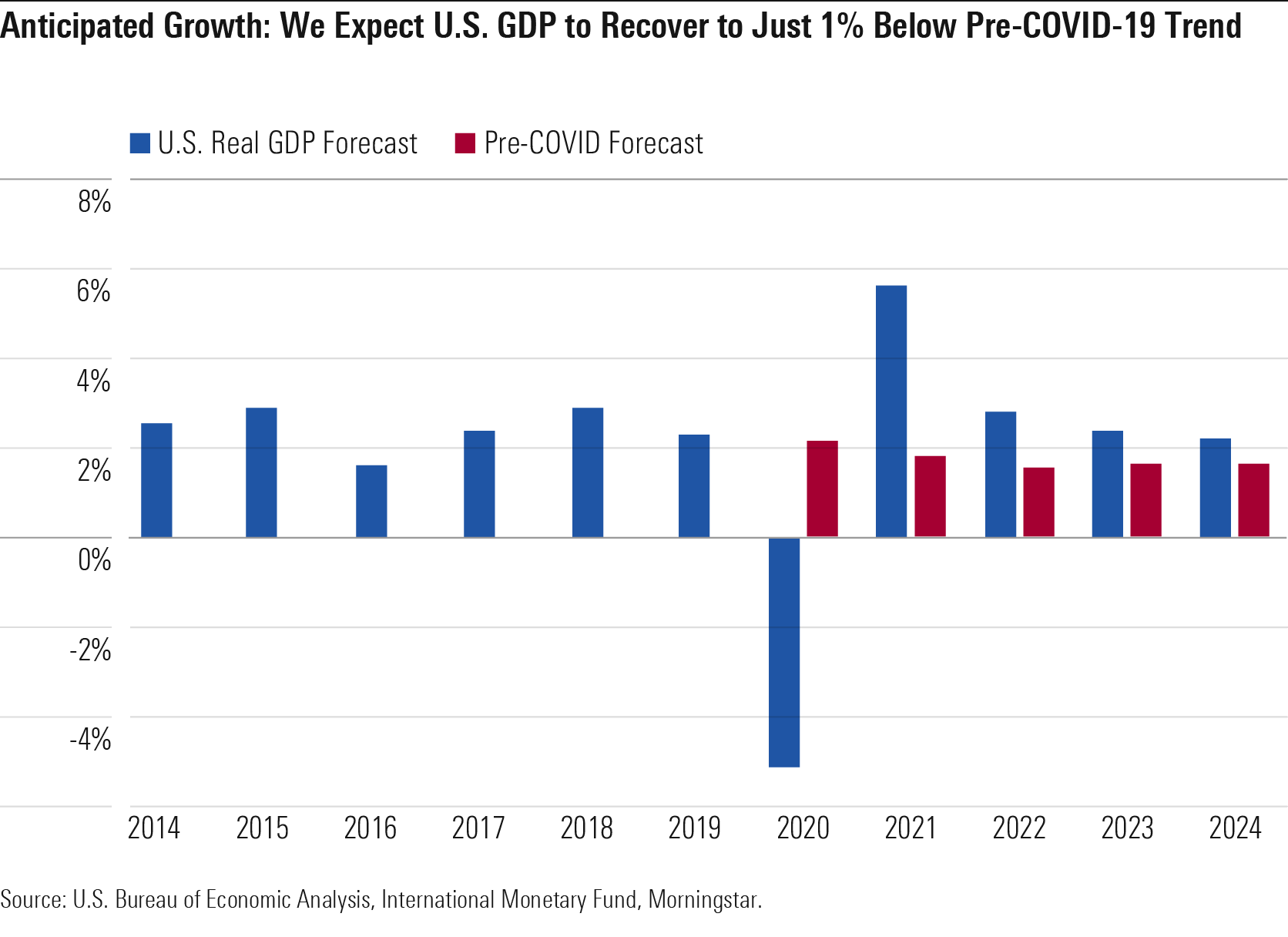

Anticipated Growth: We expect U.S GDP to Recover to Just 1% Below Pre-COVID-19 Trend

We Don't Think COVID-19 Will Lead to Economic Disaster Analysts anticipate U.S. GDP growth of negative 5.1% in 2020, about 700 basis points below our pre-COVID-19 expectation. This drop in GDP is much more severe than the Great Recession nadir of 2009. However, we expect strong catch-up growth in 2021 and the following years, such that U.S. GDP recovers to just 1% below pre-COVID-19 expectations.

We expect a very strong recovery in the second half of 2020, even as the most affected parts of the economy (restaurants and hotels) remain substantially impacted. By mid-2021, we expect output in even the most affected industries to substantially recover as the threat of COVID-19 is virtually eliminated by mass vaccination.

Even as U.S. economic activity is sharply curtailed by COVID-19 in 2020, aggressive government action is propping up private incomes and thereby helping to mitigate long-term as well as short-term damage. Thanks to fiscal stimulus (mainly the CARES Act passed in March), disposable personal income surged 11% in April versus January 2020 levels, and it was still up 6% in May. This was even as labor income was down 8% (through May) due to reduced employment.

This fiscal support has been crucial, especially given that lower-income people (with more vulnerable household balance sheets) have been hit especially hard by the pandemic in terms of job losses. Because of this impact (as well as federal forbearance rules passed in the CARES Act), residential mortgage delinquencies surged to nearly 8% in May based on preliminary data.

However, we think the initial jump in delinquencies may reflect the delayed rollout of unemployment benefits due to administrative strains from the unprecedented number of claims. Unemployment benefits didn’t really come in full force until May, and unemployment relief is targeted at the most cash-strapped people (in contrast to the stimulus checks, which were the main boost to personal income in April).

We project that domestic private income will see a 9% boost in 2020 despite the drop in GDP, thanks to the increase in the government deficit. Much of this income windfall will be saved in the near term, which will bolster household and firm balance sheets. This will curb financial distress risk and encourage higher spending once the pandemic is over.

We See Little Contagion Risk for U.S. Markets Our data shows that U.S. corporate sector leverage looks unthreatening relative to historical averages; this contrasts with the financial press' highlighting of corporate debt risks. The Bank of International Settlements has also often discussed corporate debt risks in publications during recent years. That discrepancy is partly explained by the fact that debt has increased more substantially outside the U.S. (and outside other advanced economies). World average corporate debt/GDP has increased to 95% in 2019 from 78% in 2008. This has been driven entirely by an increase in emerging markets to 99% in 2019 from just 55% in 2008.

The largest increase in borrowing has come from China, where corporate debt has surged to 149% of GDP in 2019 from 94% in 2008. Outside China, debt has increased more modestly (to 75% from 43%), and the absolute level of debt is far less threatening.

While we have long believed that China's high debt load will be a key driver in slowing its GDP growth compared with its recent history (which has implications for the global economy), we don't think this is likely to spur a global financial crisis. The vast majority of China's corporate debt is ultimately owed to Chinese households via bank deposits and other investments. As such, there's little contagion risk for the U.S. financial system. Outside China, emerging-market corporations have relied more heavily on external borrowing, which means that holders of emerging-market corporate debt overlap more substantially with holders of U.S. corporate debt. However, emerging-market bond yields don't appear distressed, at least for now, and we think the Fed should be able to maintain liquidity in U.S. corporate bond markets even if pressures increase in emerging markets.

Overall, the U.S. financial system is in a far different place than it was before the 2008 global recession, with no fragilities on par with pre-2008 shadow banking and the banking system much better capitalized. Most importantly, the monetary and fiscal policy response has been historically strong, helping to shore up any weaknesses that have arisen from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our next report will further bolster our thesis by detailing the different types of financial crises and the major risk factors for each. Those risk factors don’t indicate a high risk of crisis in the current environment.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/010b102c-b598-40b8-9642-c4f9552b403a.jpg)

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/e03383eb-3d0b-4b25-96ab-00a6aa2121de.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/LE5DFBLC5VACTMC7JWTRIYVU5M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PJQ2TFVCOFACVODYK7FJ2Q3J2U.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/KPHQX3TJC5FC7OEC653JZXLIVY.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/010b102c-b598-40b8-9642-c4f9552b403a.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/e03383eb-3d0b-4b25-96ab-00a6aa2121de.jpg)